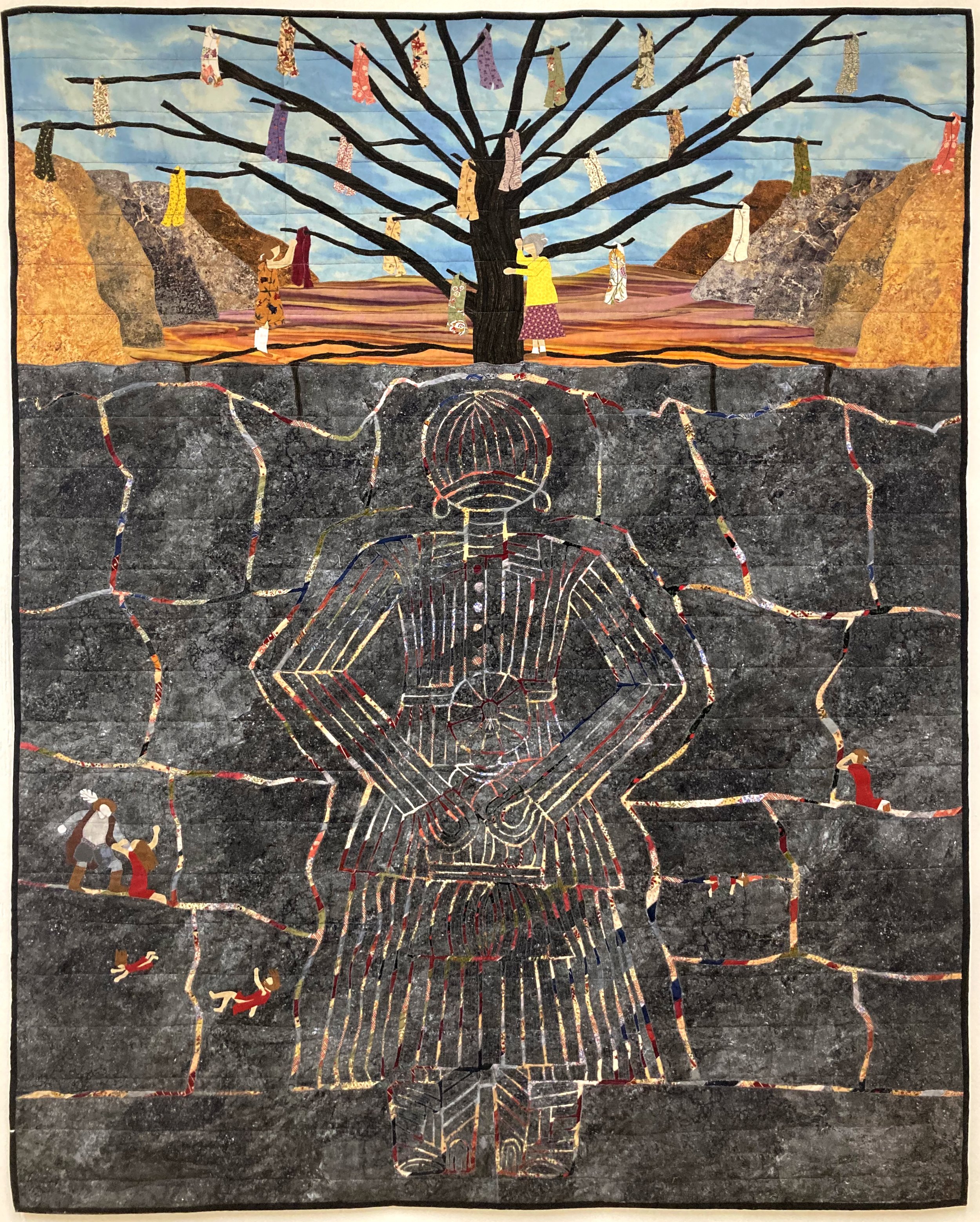

Susan Hudson (Navajo/Diné, born 1960)

MMIW: The Tree of Many Dresses, 2021

Pieced and quilted fabric

58 x 71 in. (147.32 x 180.34 cm)

MMIW: The Tree of Many Dresses is one of a series of quilts that Susan Hudson created to call attention to the epidemic of murdered and missing indigenous women, an ongoing and continent-wide crisis that touched the artist personally. The work captures Hudson’s heartbreak and outrage in the wake of the abduction and murder of her niece, eleven-year-old Ashlynn Mike, in 2016. Due to snarled jurisdiction disputes between tribal and state governments, and despite repeated protests from community members, authorities did not issue an Amber Alert until 2 am the night of the young girl’s disappearance, over eight hours after the kidnapping.1 In creating The Tree of Many Dresses, Hudson drew from dreams and prayers in the wake of the tragedy.

The roots of the tree reach toward the central image of the work: a woman comforting a young girl beneath the surface of the earth. The figures are executed in highly labor-intensive reverse-applique technique, in which the image is formed by the negative spaces between the top-most layers of fabric. They represent the enduring strength and resilience of the Navajo people; this power is etched into the geological core of the land that witnesses the lives and deaths of abducted women (fig. 1). “When you look at the mountains,” Hudson says in describing the work, “you can only see what is on the outside. But the inside, like outside, is also beautiful.”2 Hudson notes that when missing women are found, sometimes they are identified by nothing more than a scrap of their clothing, a chilling detail that resonates in the material qualities of the artwork. Here Hudson also included depictions of the injustices commited against Native women since their first encounters with European colonizers. On the left, a man in colonial garb holds a woman by the neck. Other women appear to fall away, as if tossed aside. The depiction of women as throwaway objects contrasts starkly with the tenderness of the central figures. Above the ground, dresses hang from the tree as women mourn their loved ones. The symbolism of the dresses is poignant, recalling the traditional practice of Navajo people hanging their clothing on trees to return it to the earth once it is no longer used.

Hudson learned to quilt as a child. Her mother’s uncompromising standards, molded by experiences of harsh corporal punishment at boarding school, were passed down to her daughter. The artist, who has strong ties to the Cheyenne community, began making quilts with a star pattern typically associated with Northern Plains quilters. She notes that, early on, viewers were surprised to find her producing work that veered away from weaving, basketry, and silverwork—art forms traditionally associated with the Navajo people. On the suggestion of Senator and jewelry maker Ben Nighthorse Campbell, Hudson began incorporating images into her work. She is inspired by ledger drawings, narrative images produced by Plains people during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The visual impact of these materials can be seen in the spare, powerful depictions of the figures in her quilts. Hudson’s quilts, in depicting the contemporary and historical struggles of the Navajo people, are not uncontroversial in her community for their depiction of hardships. Nevertheless, in works like The Tree of Many Dresses, the artist confronts these struggles in a manner that also celebrates her peoples’ perseverance in a materially innovative form.

1 Rachel Monroe, “The Delay: How the Kidnaping and Murder of Ashlynne Mike Changed Our Country’s Amber Alert Protocols,” Esquire, Apr 18, 2018, https://www.esquire.com/news-politics/a19561163/ashlynne-mike-amber-alert-navajo-reservation/.

2 Conversation with the artist, May 12, 2021.