Traditions

and

Transformations:

Modern and Contemporary

Native Visions

from the

Horseman Collection

INTRODUCTION

Over the course of the past century, artists of Native descent in the United States and Canada have produced dramatically varied, vibrant, and groundbreaking bodies of work, often in the face of tremendous institutional and societal adversity. Yet, despite a century-long engagement with the currents of modernism and postmodernism, art by Native peoples has been historically ignored by established cultural institutions, including fine art museums, universities, and galleries. In its mission to broaden the canon of American art, the Horseman Foundation strives to ensure that the growing number of works by modern and contemporary Native American artists from the collection of John and Susan Horseman are available to the public. Toward that purpose, this project presents essays on artworks by Indigenous artists from the collection in an effort to expand open access to critical writing on these pieces. The paintings and sculptures gathered in this digital exhibition are grouped loosely by aesthetic and social issues Indigenous artists are confronting and engaging with through their work, including the dual forces of tradition and modernity; reactions to settler colonial encroachment on Native culture; present day experiences of urban and reservation life; and visions of the future in the face of political instability and climate change.

Click to continue reading...

There are over five hundred Native tribes in the United States and six hundred in Canada that collectively speak nearly two hundred different languages and maintain distinct cultural traditions. Any broad generalization about Native art today is not only prone to missing crucial subtleties, but also to perpetuating harmful stereotypes that Indigenous people have actively sought to dismantle. Given Native artists’ multiplicity of experiences, knowledge systems, and ways of knowing—and working—a grouping of artworks such as the one presented here is, by necessity, a sampling (rather than a comprehensive survey) of the extensive scope of work produced during past seventy years. Despite these challenges, Native American art history informed by the research of Indigenous scholars has agreed on a series of key developments throughout the twentieth century that continue to resonate in the artwork and intellectual climate of modern day.

During the early twentieth century, the Southwest region of the United States served as a vital site for many of these developments. Unlike other parts of the country, the Southwest’s Native communities had largely remained on their original homelands, and these communities, along with the region’s landscape, served as major draws for Anglo-American tourists and artists alike. In Santa Fe during the 1910s, a group of residential school children, including Awa Tsireh (San Ildefonso), Tonita Peña (San Ildefonso), and, later, Fred Kabotie (Hopi) were encouraged to produce drawings of their tribal ceremonies by an Anglo-American school teacher. This development coincided with support from Santa Fe’s artist colony and ongoing efforts to record the supposedly “dying” Native culture. The patrons and teachers who fostered the creation of watercolor paintings by this group of students—sometimes referred to as the San Ildefonso self-taught group—feared that Native cultures were in danger of vanishing as a result of the cultural genocide inflicted on Indigenous communities throughout the United States and Canada. Though sympathetic to the Native people in the region, the Anglo-American supporters of Native artists were prone to what J.J. Brody concisely describes as “benevolent paternalism” and a “romantic primitivizing” of the very communities they sought to help.1 That is, the novelty, craftsmanship, and design of Native people’s art in the region alone did not satisfy the parameters set by Anglo-American patrons. There also had to be an element of rediscovery of an “ancient” technique or, in the case of paintings, imagery.2 The artists, many of them teenagers, created works with a prescribed set of strictures which were considered “appropriate” for “authentic” (that is, ahistorical and devoid of references to modernity) representations of Native experiences. A similar development occurred in Oklahoma, where a group of young artists became known as the Kiowa Six. Their work, influenced in part by Plains Native American ledger drawing traditions, was also encouraged by Anglo-American patrons and depicted tribal ceremonies and nostalgic scenes of tribal life.3 Stylistically, paintings from both regions featured flatly rendered figures with neither backgrounds nor use of linear perspective. Though artists like Awa Tsireh and Fred Kabotie initially tried to make work that incorporated perspective and other illusionistic techniques, students were strongly discouraged from the use of realism and from producing oil on canvas paintings in the academic Western style, which was considered an unsuitable form of expression for Native people.4 In Santa Fe, the source motifs used in these images were drawn from designs found on utilitarian objects used by Pueblo peoples, such as textiles and pottery, as well as the Ancestral Pueblo pottery being excavated in nearby digs led by archeologist Edgar Lee Hewett.5

The stylistic developments of the artists in Santa Fe and of the Kiowa Six were later adapted as the basis for the Santa Fe Studio School, founded in 1932 and led by Anglo-American instructor Dorothy Dunn.6 Dunn, who led the school for five years, also introduced her students to global influences through slide presentations of artworks from China, Greece, and, notably, Persia.7 Dunn pushed her students to think of art beyond the limits of commercialism, but like her predecessors, also encouraged them to draw from their “ancient traditions” and generally regarded them as "inituitive" and capable of producing artwork without instruction.8 Like the San Ildefonso group before them, many artists working in the Studio School style—including Harrison Begay (Navajo), Oscar Howe (Yanktonai Dakota), Joe Herrera (Cochiti Pueblo), and Gerald Nailor (Navajo)—displayed exceptional talents for draftsmanship and produced a new type of painting that holds a singular place in the history of twentieth American art. It speaks to the success of their talents and of Dunn’s efforts at publicizing their work that these paintings were exhibited in dozens of shows nationally and abroad during the 1930s. Nevertheless, graduates from the Studio School were immediately forced to make work for the tourist market of White consumers. Many were aware of their patron’s ignorance of Native culture, and painters like Nailor often made work which appeared to depict tribal ceremonies, but were, in reality, imagined fabrications (fig. 1).9 The most successful artists from this period strove to continue their education at non-segregated schools and to distance themselves from the rigid stylistic mode of the Studio School.10

gouache on board, 14 3/4 x 13 in. (37.47 x 33.02 cm)

The John and Susan Horseman Collection

Simultaneously, exhibitions throughout the United States were introducing new audiences to Native American art. Touring shows such as the 1931 Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts, organized by painter John Sloan and wealthy socialite Amelia Elizabeth White, sought to reposition Native arts as aesthetic rather than ethnographic material bound for the likes of the American Museum of Natural History. 11 A decade later in 1941, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), under director Rene d’Harnoncourt, mounted Indian Art of the United States, a wildly popular exhibition that drew further attention to the artistic production of Native peoples. Though deeply problematic by contemporary standards, these exhibitions were a watershed in the general public’s interest in and appreciation of Native American art.12 Concurrently, the tremendous focus on what was deemed to be “authentic” Native art stymied the careers and aspirations of many artists who were either uninterested in making work in the Studio School style or sought to move beyond its restrictive parameters, such as painter Oscar Howe and sculptor Allan Houser (Chiricahua Apache).13 And in New York, artists such as George Morrison (Ojibwe) and Leon Polk Smith (Cherokee) were producing abstract paintings with few overt nods to their Native heritage. As scholar Richard Hill (Tuscarora) points out, these painters’ embrace of modernism was seen as a “mark of assimilation” which negated their Indigeneity.14 Nevertheless, many critics continued to search for the “Indian essence” in their work.15 As has been the case with many artists from that period who were not white men, scholars and critics have only recently revisited these artists’ work for its innovative contributions to the language of American abstraction.

Despite the talents of painters working in the Studio School style, Indigenous artists and supporters of Native art were keenly aware of fact that the institution taught its students to produce work in a mode imposed by Anglo-Americans and heavily associated with tourist markets. Dissatisfaction with the pedagogy of the Studio School led to its dissolution and, in 1962, to the creation of the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in its stead—and on its old grounds. Using funding provided by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the school was founded by Cherokee artist, fashion designer, and scholar Lloyd Kiva New (fig. 2) with the help of d’Harnoncourt and drew Native students from throughout the United States. The IAIA embraced a philosophy of celebrating cultural difference and harnessing traditional Native artforms toward modernist ends. Its establishment changed the course of Native American art and precipitated a period of remarkable creativity in new forms of artistic media, yet its goals were, from the outset, also aligned with the integration of its student body to the dominant, Anglo-American culture. As Joy L. Gritton has pointed out, though the school projected an image of stalwart pluralism and encouragement of diversity, its pedagogy strongly favored Western modernist aesthetics that were centered on individual achievement, as well as monetary success in the mainstream commercial art market.16 These goals were a distinct deviation from the community-centered tribal philosophies which informed many of the students lives outside of the IAIA. Like work by Studio School pupils before them, students’ work was exhibited nationally and internationally, this time under the pretense that its creators had never encountered modern art. Publicity surrounding these exhibitions suggested that the artists’ impulses toward abstraction were a spontaneous product of their cultural upbringing, when, in fact, instructors used slides of modern artworks provided by MoMA and texts by authors such as Susan Sontag.17 As such, the legacy of presenting Native artists as anachronistic and out of touch with contemporary developments continued to hold sway. In reality, many students and their teachers, including painter Fritz Scholder (Luiseño), were knowingly contending with the dualities of their cultural experiences and the mainstream artistic and intellectual landscape of the mid-twentieth century.

Sand and mixed media on canvas, each 46 x 32 in. (116.84 x 81.28 cm)

The John and Susan Horseman Collection

Expectations that Native artists produced work that satisfied audiences’ race-based expectations prompted some artists—including George Morrison, Leon Polk Smith, and Fritz Scholder—to disavow themselves of being considered “Indian artists.” With this stance, artists sought to distance themselves from the work typically associated with Indian markets and tribal craft traditions—as well as from regional styles—and to position themselves as active participants in an artworld that fetishized internationalism and “universality” as its highest standards. Today, scholars note the profound inequity of the binary between Native art and mid-century modernism during this time. For instance, Hill observes that Native artists working during this period were trapped in a vicious catch-22: if they created objects in traditional mediums, their work was considered outside the sphere of fine art, and if they produced art in line with the expectations of post-war modernism, critics took note of how much they had integrated with the dominant culture.18 By the 1980s, Native artists and curators challenged these artificial divisions through exhibitions that sought to expand the narrow definitions of what could and could not be considered “Native” and “modern.” The early 1980s exhibitions New Work by a New Generation in Regina, Canada and Contemporary Native American Art in Stillwater, Oklahoma paved the way for a wider understanding that traditional art, cultural specificity, and modernity could not only be reconciled, but synthesized into new forms. These exhibitions and the published texts that accompanied them insisted on the fact that an artist’s references to their Native background in no way excluded their work from the contemporary artistic discourse. A few years later and with the growing influence of the Women’s Movement, Women of Sweetgrass, Cedar, and Sage, a 1985 exhibition organized by artists Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation) and Harmony Hammond, further expanded on these ideas by focusing specifically on Native women as a vital players within larger artistic landscape of the United States.19 Firmly postmodern in their outlook, the impacts of these ideas contributed to the shape of emerging artistic sensibilities of the late twentieth century and continue to resonate in the mainstream contemporary art world today.20

In 1992, celebrations of the five-hundred-year anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in North America prompted a number of Native-led exhibitions that simultaneously called attention to the genocide of Indigenous people and further enlarged the audiences for contemporary Native art. Perhaps the most direct rebuke came in the form of the exhibition, Submuloc Show/Columbus Wohs, organized by Quick-to-See Smith, which showcased work by contemporary Native artists including Kay WalkingStick (Cherokee), Duane Slick (Meskwaki), Jean LaMarr (Northern Paiute/Achomawi), James Luna (Luiseño), and others at twelve venues over the course of two years. The innovations taking place within the Native artistic community throughout the past decades was, at that point, not lost on the mainstream academics.21 That fall, Art Journal, released an issue solely devoted to critical essays on contemporary Native art in the United States and Canada, which included essays by WalkingStick and Luna, as well as scholars of Native American art. Simultaneously in Canada, Land Spirit Power: First Nations at the National Gallery of Canada and Gerald McMaster’s (Siksika Nation) exhibition Indigena: Contemporary Native Perspectives in Canadian Art at the Canadian Museum of Civilization were among the first exhibitions that placed this material within major institutional frameworks, decades ahead of similar developments in the United States.

The breadth of mainstream and scholarly attention paid to contemporary Native artists during the early nineties and the comparative dearth of it in the years that followed must serve as a lesson for our time. Renewed awareness of the artistic contributions of Black, Indigenous, Asian, and Pacific-Islander artists over the past decade has been a much-needed corrective to the historical understandings and canon of American art. Yet, it is key for future academic and popular histories of American art that work by Native and Indigenous people be understood as an integral aspect of the evolution of modernism and postmodernism. Scholar Janet Berlo has pointed out that, as late as 2015, museum curators omitted modern and contemporary Native American art from American art galleries as standard practice, and works by artists such as Jaune Quick-to-See Smith hung next to archeological objects, rather than with the work of her contemporaries.22 The larger fabric of American art history is woefully incomplete without the contribution of Native artists’ work within its narratives. “At every moment in our young nation’s history,” Berlo writes, “Native art was part of a cosmopolitan conversation, one that stretched beyond reservations, regions, and nations.”23 The works presented in this project exemplify that cosmopolitanism and worldliness as it has evolved over the past seventy years. Representing twenty eight artists from nineteen tribal backgrounds working in mediums as diverse as painting, ceramic, bronze, wood, and textiles, Traditions and Transformations offers a glimpse of the vision and innovativeness of Native artists across the United States and Canada.

1. J.J. Brody, Indian Painters and White Patrons, (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1971), 48-9.

2. Ibid, 70.

3. Ibid, 176-8.

4. Ibid, 92-6.

5. For an extensive discussion of this period of Native modernism, see J.J. Brody, Pueblo Indian Painting: Tradition and Modernism in New Mexico, 1900-1930, (New Mexico: School of Advanced Research Press, 1997). The Anglo-American patrons such as Hewett and Kenneth Chapman also encouraged the decoration, commercialization, and sale of Pueblo pottery, in particular, to the burgeoning tourist market flourishing in Santa Fe.

6. Bruce Bernstein and Jackson Rushing, Modern by Tradition: American Indian Painting in the Studio Style, (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995), 27.

7. Bernstein and Rushing, Modern by Tradition, 40-41.

8. Brody, Indian Painters, 131.

9. Ibid, 132.

10. Ibid, 140-46.

11. On White and Sloan, see Gregor Stark and E. Catherine Rayne, El Delirio: The Santa Fe World of Elizabeth White, (New Mexico: School of Advanced Research, 1998).

12. On this exhibition, see Paul Chaat Smith’s critical analysis in “Indian Art for Modern Living” in Mindy Besaw, et al, Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950 to Now, (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2017), 96-99.

13. Bill Anthes, Native Moderns: American Indian Painting, 1940–1960, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 158-170.

14. Richard Hill, “I Am an Artist Who Happens to Be an Indian: Working through Modernism in the 1970s and Early 1980s” in Mindy Besaw, et al, Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950 to Now, (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2017), 52.

15. Anthes, Native Moderns, 144.

16. Joy Gritton, “Cross-Cultural Education vs. Modernist Imperialism: The Institute of American Indian Arts” in Art Journal 51, no. 3 (Autumn, 1992), 28. See also Gritton’s monograph-length study on the IAIA, Joy Gritton, The Institute of American Indian Arts: Modernism and U.S. Indian Policy, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000).

17. Ibid, 29.

18. Richard Hill, “I Am an Artist Who Happens to Be an Indian,” in Art for a New Understanding, 54.

19. Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and Harmony Hammond, Women of Sweetgrass, Cedar, and Sage, (New York: Gallery of the American Indian Community House, 1985).

20. Hill, “I Am an Artist Who Happens to Be Indian,” in Art for a New Understanding, 58.

21. Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, The Submuloc Show/Columbus Wohs: A Visual Commentary on the Columbus Quincentennial from the Perspective of America’s First People, (Phoenix: Atlatl, 1992).

22. Janet Berlo, “The Art of Indigenous Americans and American Art History: A Century of Exhibitions,” in Perspective 2 (December 7 2015), 5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/perspective.6004

23. Ibid, 6.

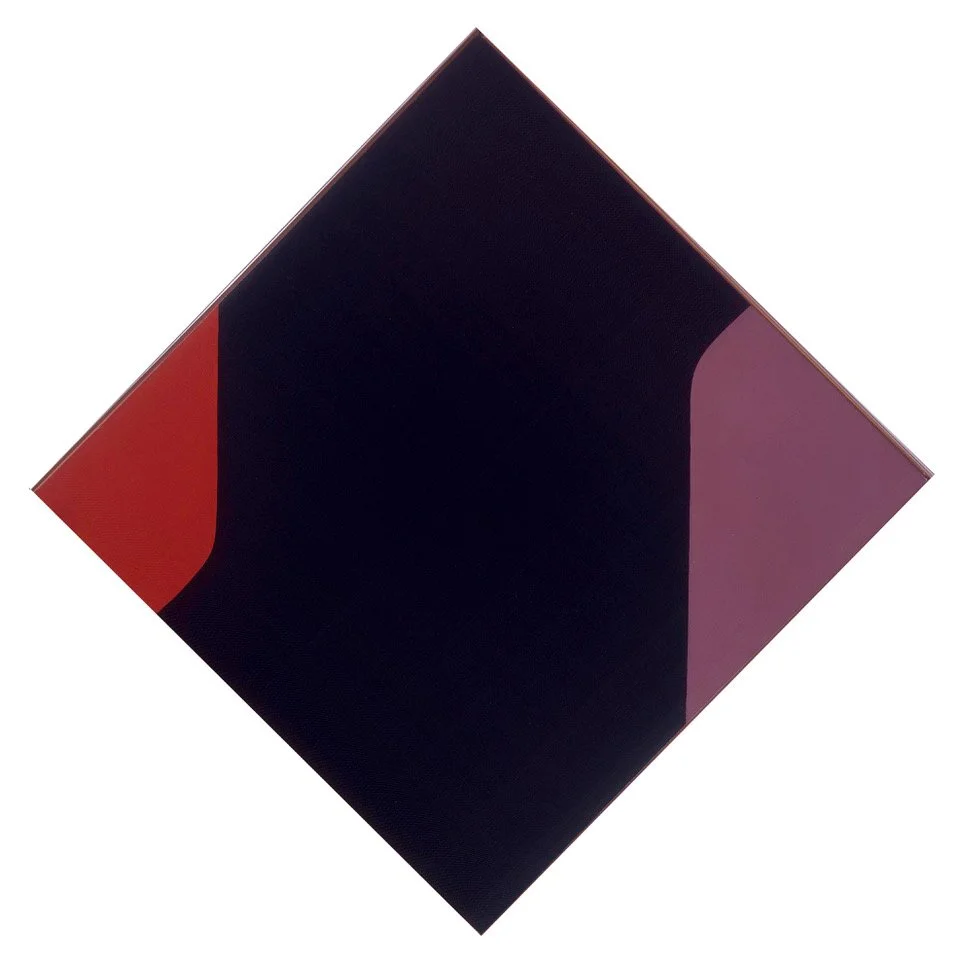

Abstractions

Abstraction has been a fundamental element of Native American art for centuries prior to its widespread acceptance in the mainstream commercial art world in the mid-twentieth century. Yet, for much of the first half of the twentieth century, interest in fine art by Native artists was limited almost exclusively to the figurative style developed in Santa Fe and Oklahoma during the 1920s. By mid-century, artists like Allan Houser were challenging this paradigm by developing work that drew from modernist and global influences. In keeping with the universalist philosophies that so often accompanied attitudes about modern art, some artists represented here vehemently separated their racial background from their creative practice. Throughout the second half of the twentieth century and due in part to the Institute of American Indian Arts, countless Native American artists adapted the language of twentieth century post-modernism and formal abstraction to articulate their ideas.

Images below link to catalogue entries

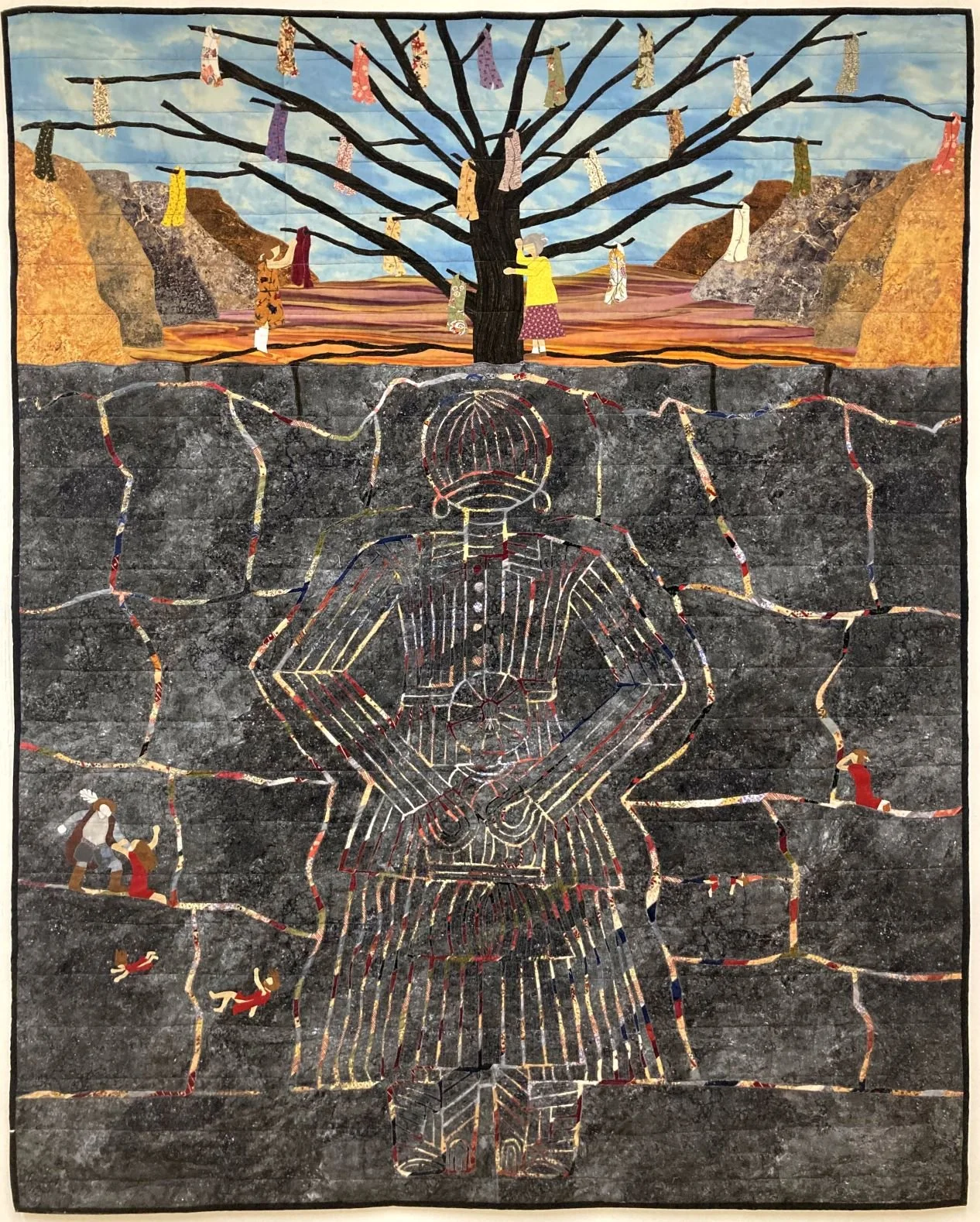

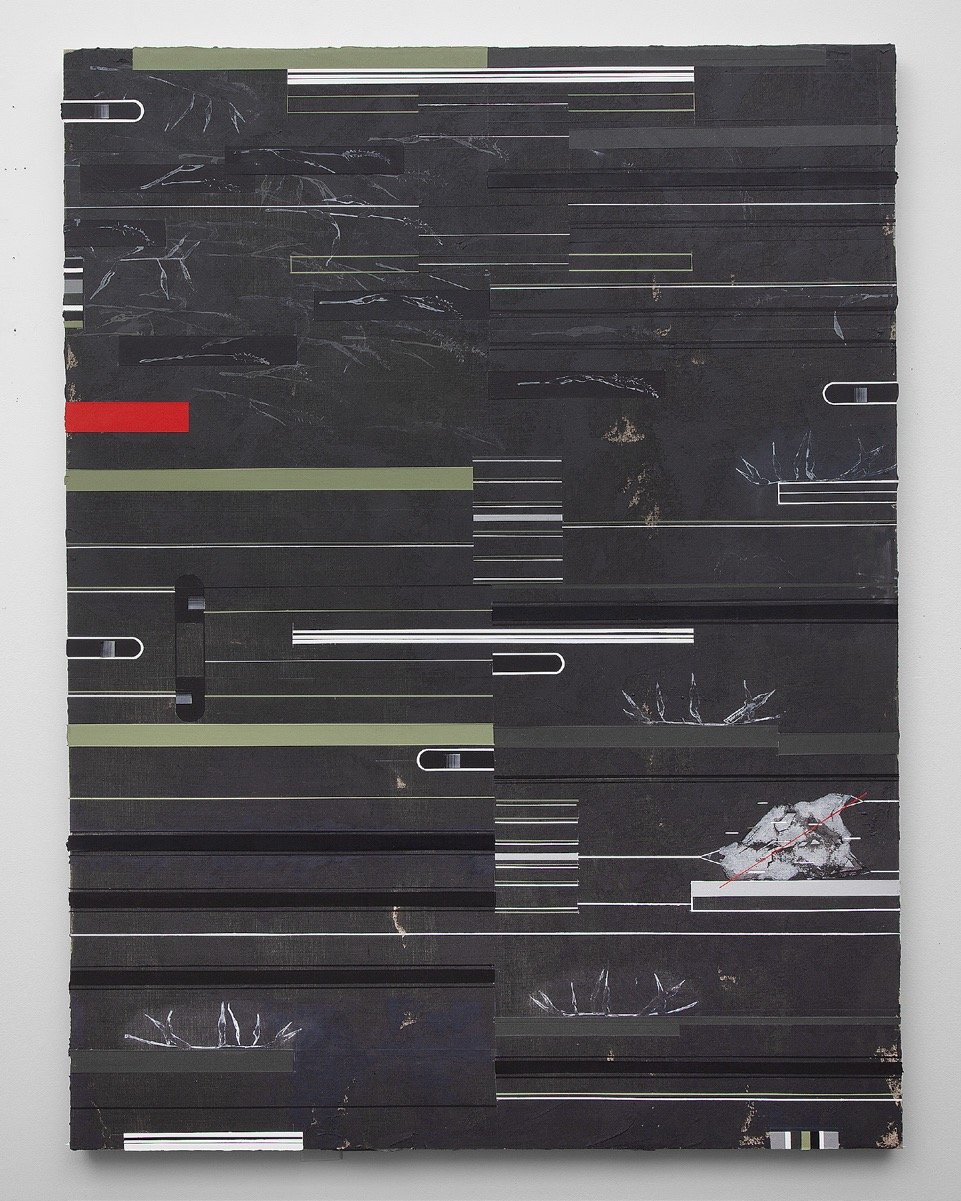

Critiques

In 1999, Chippewa philosopher Gerald Vizenor coined the term survivance—a portmanteau of “survival” and “endurance”—to describe the ongoing perseverance of Native individuals and communities against the existential pressures of colonization. Native peoples’ resistance to these pressures manifests in the work of numerous artists represented in this project. Their works interrogate the settler-colonial legacy, expose the injustices facing Indigenous people, and celebrate the tenacity of their living cultures.

Images below link to catalogue entries

Juane Quick-to-See Smith

Indian Hand, 1990

Susan Hudson

MMIW: The Tree of Many Dresses, 2021

Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun Lets'lo:tseltun

Leaving My Reservation, 1985

Julie Buffalohead

Turn a Blind Eye, 2014

Marianne Nicolson

Tunics of the Changing Tide: Kwikwasut’inuxw Histories Double Headed Thunderbird Design, 2007

Marianne Nicolson

Tunics of the Changing Tide: Dzawada’enuxw Histories Tree of Life Design, 2007

Roxanne Swentzell

The Corn Mothers Are Crying, 2015

Cosmologies

Indigenous artists throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have explored the beliefs and traditions of their communities—and the impact of the modern world on those beliefs—through their work. Traditional Native religious beliefs and oral histories survive today in spite of unrelenting pressures exerted on Indigenous peoples by the settler-colonial culture in the centuries following contact. While gouache and watercolor have been used by Native artists to depict cultural ceremonies since the 1910s, many contemporary artists have embraced easel painting in acrylic and oil, once considered an Anglo-American convention, to depict their religious and spiritual beliefs, while others work in three-dimensional media with long histories and traditional associations.

Images below link to catalogue entries

Realities

In cities, on reservations, and in the milieu of digital realities, works in this section focus on Native artists’ reactions to the excitement and banality of modern life. Themes here range from interpretations of Hollywood portrayals of Native Americans to the challenges of reconciling Indigenous heritage with consumerist desires. A far cry from the romanticized and ahistorical popular notions of Native American artwork that held sway for much of the twentieth century, these works are profoundly a product of their temporal circumstances, from the late 1970s to present day.

Images below link to catalogue entries

Futures

Indigenous artists working today are increasingly drawing from themes of science fiction and futurism in their work. In the face of climate change and global political instability, these artists are imagining what the next decades will look like, often with a wary dash of hope.

Images below link to catalogue entries

The Horseman Foundation is located in Saint Louis, which is on the traditional territories of the Osage Nation, Missouria, and Illini Confederacy, who have stewarded this land throughout the generations. We honor them for their legacy and ongoing contributions to the history of this region.

About the Authors

Aleta M. Ringlero is an enrolled member of the Salt River Pima Indian Community, Scottsdale, AZ where she resides since moving from Washington, D.C. where she directed Native American Public Programs for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. An art historian by education, Ringlero has held positions as varied as Exhibit Research Specialist for the California State Railroad Museum, Sacramento, to archeological resources coordinator, Tahoe National Forest, Nevada City, CA. She has developed public collections of indigenous art for Casino Arizona and Talking Stick Resort, Scottsdale, Coyote Valley Casino, Healdsburg, CA. and Snoqualmie Casino outside Seattle, WA. Curator, author, calligrapher, and saddlemaker’s daughter, Ringlero multi-tasks by attempting Italian cooking and studying the Russian Cyrillic alphabet on YouTube.

Anastasia Kinigopoulo is the Director and Curator of the Horseman Foundation. Previously, she was a Lois F. McNeil Fellow in the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture and served as the Assistant Curator at the Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio. In the latter role, she worked on numerous exhibitions, including I Too Sing America: The Harlem Renaissance at 100, A Dangerous Woman: Subversion and Surrealism in the Art of Honoré Sharrer, and Art After Stonewall: 1969-1989, which won the 2020 AAMC Curatorial Award for Excellence. She also served as the editor for a number of the museum’s publications. In addition to her art historical training, Kinigopoulo holds a BFA from the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, where she studied oil painting and etching.