Emma Amos

Like many of her predecessors and peers, the multimedia artist and painter Emma Amos (1938-2020) grappled with developing her own artistic voice while navigating traditional art training based on European models both in the United States and in England. Although she was initially attracted to abstraction through her exposure to the Abstract Expressionist movement during part of her undergraduate studies in London, U.K., upon her return to the United States, Amos pivoted permanently to figuration, stating: “...when I came back to New York and had joined Spiral [an arts collective], I returned to the figure, and I’ve never stopped since.”1 10 In continually working with and between drawing, painting, textile and printmaking within her practice, Amos resisted strict categorization by utilizing varying forms of media, and rejected membership to any one artistic group or movement during her lifetime.

In much of the artist’s historiography, Amos is mentioned alongside the influential and oft-cited Spiral arts collective of the 1960s. Active between 1963 and 1966, Spiral boasted members such as renowned artists such as Romare Bearden (1911-1988), Charles Alston (1907-1977) and Norman Lewis (1909-1979). Amos was both the youngest member and the only woman admitted into the group, in large part due to the encouragement of Spiral member Hale Woodruff (1900-1980). Curiously, while many of the members knew or knew of equally-established Black female artists such as Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012) or Augusta Savage (1892-1962) (the latter with whom both Bearden and Lewis studied), no other woman received an invitation to join the collective. With the exception of several meaningful examples of artistic mentorship and guidance during her time in the group, Amos characterized the collective as dominated by sexist attitudes, which led her to the conclusion early on that the New York art world was “a man’s scene, Black or white.”2 While Spiral provides some context around Amos’ position in the arts movements at-large at that time, her desire to speak more explicitly to the intersection of gender and race found refuge elsewhere starting in the 1980s, such as in her membership to the feminist art groups the Guerrilla Girls and the Heresies Collective.3 On the cusp of Spiral’s dissolution – which scholars have mostly attributed to divergent opinions regarding the collective’s purpose, membership and future, along with irreconcilable creative differences – Amos produced Three Figures (1966), a work that typifies many of the themes and questions the artist grappled with throughout her life.4

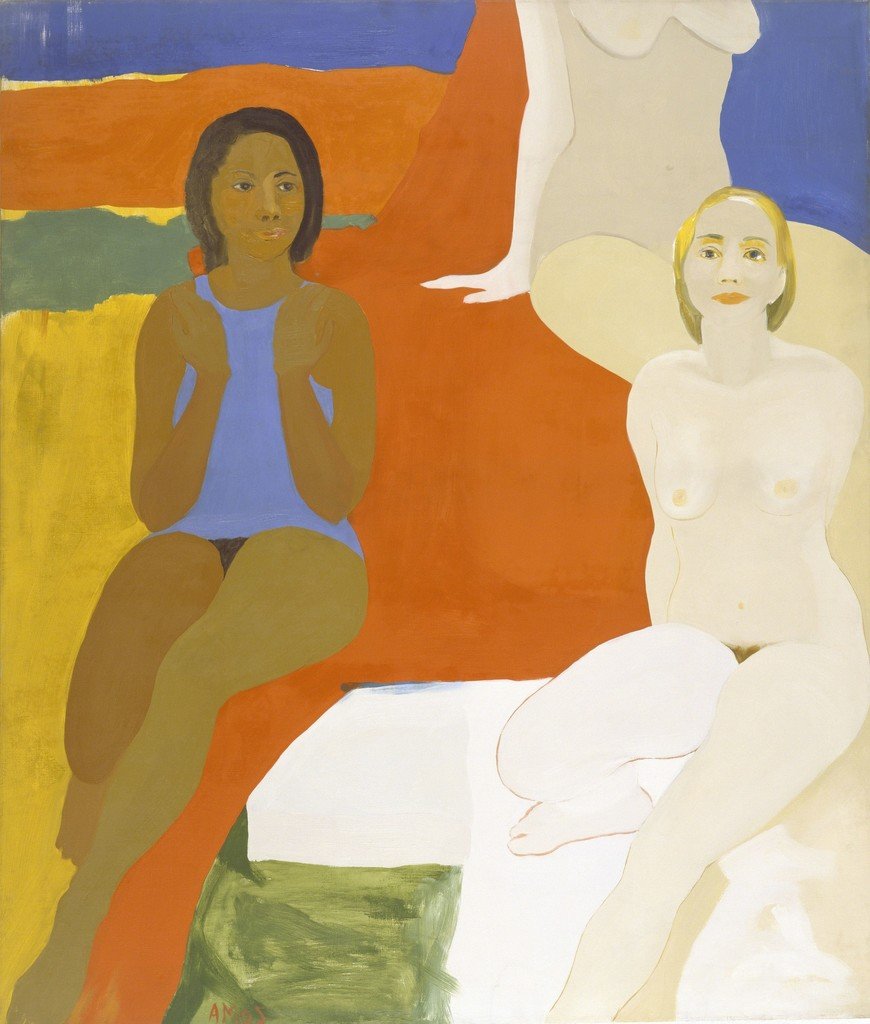

Utilizing a palette reminiscent of the French post-Impressionist artist, Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), Amos’ dark oranges, yellows, greens and blues dominate the canvas of Three Figures. Depicting a trio of women of varying complexions, the primary figure on the left has long, dark hair and caramel skin. The other two women – both of whom are partially obscured – have light beige and yellow skin, and the woman occupying the center has blonde hair and light-colored eyes. All three sit on abstracted color blocks and are either partially or entirely nude. The gazes of the two figures featured most prominently fail to meet one another, although the sight line of the figure in the center has the potential to meet that of the viewer. Similar in composition and palette to other paintings by Amos, the specific identities of the women in Three Figures remain a mystery. Who are these women, to us and to one another? Amos does not provide a clear answer to her audiences; rather, one might consider the possibility that the painting – and so much of her practice – highlights the importance and complexity of female friendships, sisterhood and broader familial ties that transcend the societal hierarchies assigned to those of different skin colors.

Amos’ parents, India DeLaine Amos and Miles Green Amos, were themselves cousins, and while she had a fairer complexion and characterized her own ethnic background as “African, Cherokee, Irish, Norwegian and God knows what else,”5 Amos always self-identified as a Black woman. Almost exclusively depicted Black and brown women in her work, Amos resisted the impulse to create flat, one-dimensional personifications of Black people. In a 1995 interview with writer bell hooks (1952-2021), Amos reflected on her decision to challenge the traditional or stereotypical visual representations of Blackness, stating: “ I think I did what a lot of figure painters do, which is to paint what they wish or want. I remember the first time I noticed that I wasn't painting what I really knew was when I realized that I made all my figures much darker than I was. That's because I had internalized Blackness. I always felt like a Black artist, and I felt that I should only depict Blackness.”6 In questioning what it meant to paint Blackness, Amos utilized a full range of colors, hues and shades, ultimately destabilizing the notion of any one idea or type of “authentic” Blackness.

Both paintings by Amos in The John and Susan Horseman Collection – Three Figures (1966) and Yo Man Ray Yo (2000), which were produced more than thirty years apart – exemplify Amos’ determination to depict Black and brown figures who counter the notion of singular or monolithic Blackness, and instead showcase Black people as both varied and worthy of fair representation on the canvas. On occasion, Amos would employ the techniques and compositions of esteemed white male European or Euro-American artists, as exemplified in Yo Man Ray Yo (2000). Amos’ Yo Man Ray Yo is a direct response to the famous photograph, Noire et Blanche (2006) by Dadaist and Surrealist Man Ray (1890-1976). Currently housed at the Reina Sofia in Madrid, Spain, Noire et Blanche depicts a white-presenting woman holding what appears to be a traditional African mask. Appropriating Man Ray’s composition into her own mixed-media piece, Yo Man Ray Yo, Amos instead alters the mask to become a bust of a Black woman. In this period, many Black American artists experimented with inserting Black bodies into well-known European drawings, paintings and sculptures as a way of reclaiming the subservient or nonexistent roles of Black subjects in art. Borrowing, altering and rearranging European canonical images, sometimes through a humorous lens, are some of the tactics used by Amos throughout her practice.7 Like many of Amos’ works, Yo Man Ray Yo incorporates textiles, a medium with which Amos used frequently; throughout her career, she often pulled Kente, Kanga and Bogolanfini cloth and textiles from West and East Africa into her work. Supplementing the central image, the recognizable African fabrics served as complements to the compositions in the foreground of the stretched canvases.8

Early in her career, Amos realized that the notion of “Black art” or a unique “Black” aesthetic was one that needed serious reconsideration. Known for depicting women of color in a range of skin tones (as exemplified in Three Figures), Amos was committed to challenging both the primacy of abstraction at the time (with the rise of the Abstract Expressionist movement) and the flattening of Black art and arts practitioners. While Amos’ practice exclusively dealt in the realm of figuration – unlike the work of many of her Black artistic peers, such as Alma Thomas (1891-1978)– her dedication to expanding the representation of Black figures remained a constant in her art practice, functioning as both a pure distillation and extension of her life.

Heather Nickels

1 Courtney J. Martin, “Emma Amos in Conversation with Courtney J. Martin,” iNka:Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 30 (2012): 104-113, muse.jhu.edu/article/480717 (Accessed 17 July 2023).

2 Lisa E. Farrington, “Emma Amos: Art as Legacy,” Woman’s Art Journal 28, no. 1 (2007): 4, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20358105 (Accessed 19 July 2023).

3 Holland Cotter, “Emma Amos, Painter Who Challenged Racism and Sexism, Dies at 83,” New York Times, May 29, 2020 (Updated June 4, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/29/arts/emma-amos-dead.html (Accessed 20 July 2023; Mildred Thompson, “Interview: Emma Amos,” ARTPAPERS 19, no. 2 (March/April 1995), artpapers.org/emma-amos/ (Accessed 27 August 2023).

4 bell hooks, Interview of Emma Amos by bell hooks (New York: Hatch Billops Collection, 1995): 32-46.

5 Cotter, “Emma Amos, Painter Who Challenged Racism and Sexism, Dies at 83,” New York Times, May 29, 2020 (Updated June 4, 2020).

6 hooks, Interview of Emma Amos by bell hooks, 33.

7 Phoebe Wolfskill, “Love and Theft in the Art of Emma Amos,” Archives of American Art Journal 55, no. 2 (2016): 46–65, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26566606 (Accessed 16 July 2023).

8 Farrington, “Emma Amos - Bodies in Motion,” The International Review of African American Art 21, no. 2 (01/01/2007): 32-44 (Accessed 17 July 2023).