Nellie Mae Rowe

Nellie Mae Rowe (1900-1982) was born in 1900 and lived much of her life outside of Atlanta. A precocious and artistically talented young woman, she ran away from her family and married her first husband, Joe Wheat, when she was sixteen, in part to escape the drudgery and endless chores of her family’s farm.1 The couple moved to Vining, Georgia, a rapidly developing rural suburb on the outskirts of Atlanta, where they joined a small community of African American families. After Wheat died in 1939, she married Henry Rowe, an older man with whom she built the house she would live in for the rest of her life, and began doing domestic work for the Smiths, a local white family. Henry Rowe died in 1947, and though she spoke positively of her work for the Smiths to her white biographers, after their deaths in the 1960s, Rowe swore off domestic work—for employers, for a husband, for anyone—and chose to dedicate herself wholly to her artistic practice.2 In doing so, she created a sprawling oeuvre of sculptures and phantasmagorical works on paper while simultaneously transforming the home she built with her late husband into her “Playhouse,” an immersive art environment that quickly attracted the attention of local residents and art world figures, including Betye Saar, Herbert Hemphill, and Beverly Buchanan.3 By 1978, only four years prior to her death, she had begun working with Atlanta art dealer Judith Alexander, who provided her with art supplies in addition to exhibiting Rowe’s work at her gallery.

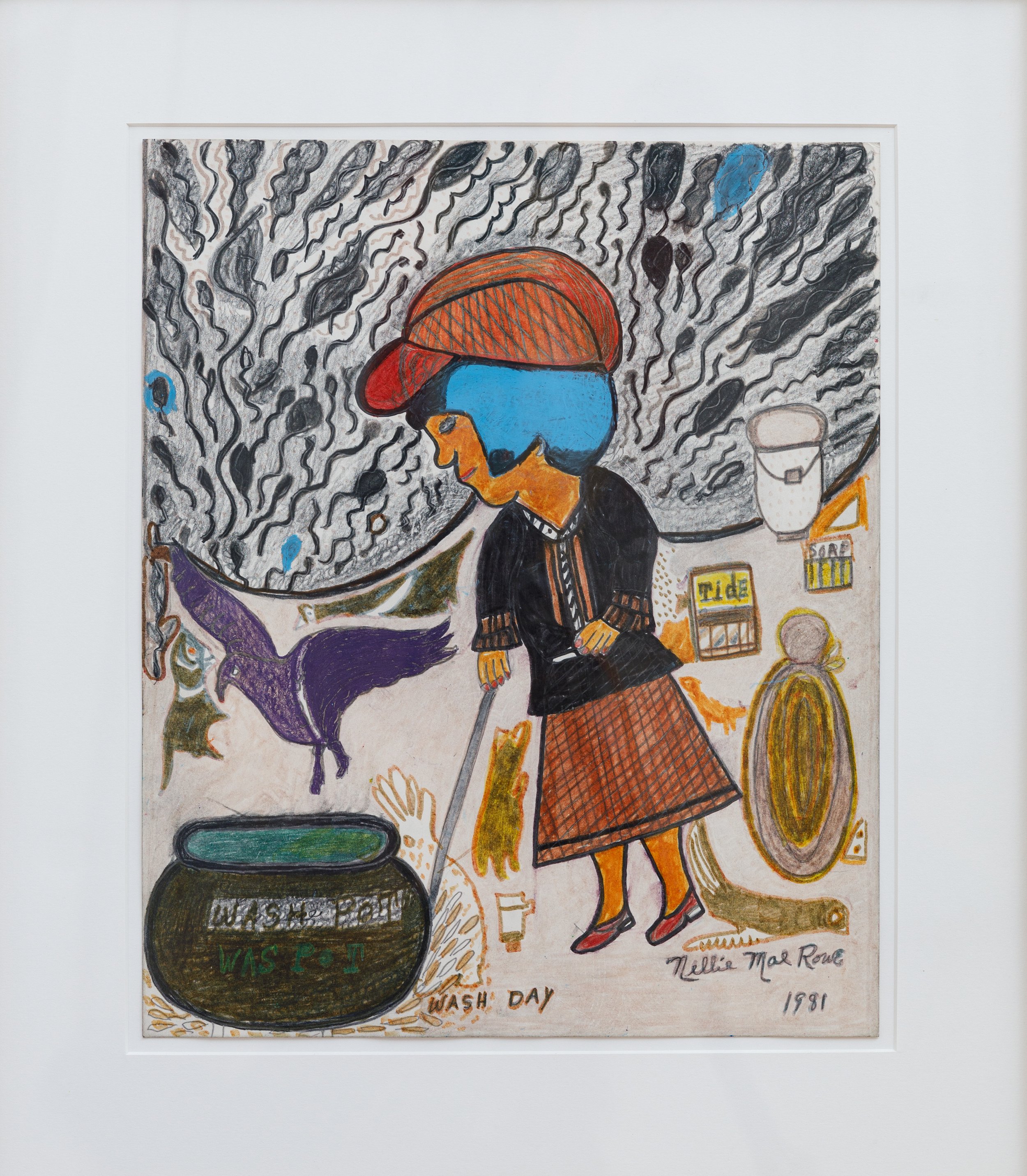

Rowe executed Wash Day in 1981, well into the era of electric washing machines. The artist would have had many first-hand experiences with wash days, a practice which began in the mid-19th century and stretched well into the 20th. Typically a Monday, the wash day entailed boiling water in a large cast iron cauldron before dispersing it into buckets. Each article of dirty clothing would have been individually scrubbed by hand on textured wash boards and line dried. Wash days were so grueling that even lower middle-class families frequently opted to hire out the chore, often to impoverished Black women who would earn a few dollars a week for their labors.4 Atlanta employed the greatest number of domestic servants (including “washer women”) per capita, and Southern states were slower to take up technological advances of the North, which moved the practice of washing clothes out of backyards and into laundromats and women’s private spheres.5 By the mid-20th century, the practice was an anachronism. Wash days are a recurring motif in the work of another Southern self-taught Black artist, Clementine Hunter, whose work dealt more directly with the practice in contrast to Rowe’s imaginative treatment of the subject seen in this piece.

Perhaps an autobiographical character, the figure in Wash Day is as intractable in her attitude towards the task at hand as Rowe herself was to the domestic work that took her away from her artistic practice. She pokes at the fire listlessly while birds and other hybrid creatures float in the air around her. Her painted nails, bright red shoes, and decoratively trimmed sweater seem especially ill-suited to the undertaking. As if anticipating contemporary viewers’ lack of familiarity with the particulars of wash days, Rowe helpfully labeled the “wash pot,” which sits next to adjacent boxes of Tide Detergent and soap. Though the piece is arguably a memory painting, Rowe’s trademark integration of surrealist elements lends the scene a dreamlike gauze and sense of playfulness in what is nevertheless a mature vision.

Several scholars have commented on the latent sexual imagery in Rowe’s paintings, and like many of the artist’s works, Wash Day is replete with subtle, yet unmistakable, innuendo.6 The bird-like creature that has emerged from the woman’s skirt caresses the back of her leg with its tail in a gesture that recalls the winged helmet of Goliath in Donatello’s sexually charged depiction of David. Simultaneously, the gray mass above her initially reads as smoke or steam but is more likely a tree, much like the one in another 1981 work which is now in the collection of the High Museum. As curator Kathrine Jentelson has pointed out, the tree in the High Museum work is strikingly phallic, while in Wash Day the foliage of the tree bares uncanny resemblance to sperm which, enlarged to immense proportions, swim upwards and away from the figure.7 Together with the woman’s discordant attire, these allusions suggest not only a desire for freedom, but also a profound longing—for a companion, for touch, or perhaps even for children, whom Rowe adored but never had herself. Like many of Rowe’s works, the piece combines memory and fantasy into a deeply personal humanist vision. Unable to attend to her artistic ambitions until the latter half of her life, the artist captured in works like Wash Day the insatiability of creative yearning that was the driving force of Rowe’s prolific last years.

Anastasia Kinigopoulo

1 For biographical information on Rowe, see Lee Kogan, The Art of Nellie Mae Rowe: Ninety-Nine and a Half Won’t Do, (New York: The Museum of American Folk Art, 1998), 16-18, and Katherine Jentelson et al, Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe, (Atlanta: The High Museum of Art, 2021), 16-19.

2 Jentelson, 19.

3 Jentelson, 22.

4 See, for instance, Sadie B. Hornsby, and Sarah Hill, “Bea, The Washwoman” (Georgia, 1939), Library of Congress, Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/wpalh000519/ For an account of the labor entailed in washing clothes see Sadie B. Hornsby, and Sarah Hill, “Bea, The Washwoman” (Georgia, 1939), Library of Congress, Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/wpalh000519/. The interviewee notes that as early as the 1930s, laundromats and washing machines were eating into the earnings of women who made money washing clothes by hand.

5 Tera W. Hunter, “The ‘Brotherly Love’ for Which This City is Proverbial Should Extend to All,” in Joe W. Trotter, ed., The African American Urban Experience: Perspective from the Colonial Period to the Present (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 83.

6 See, for instance, Jentelson, 33 and Kogan, 21.

7 Jentelson, 33.