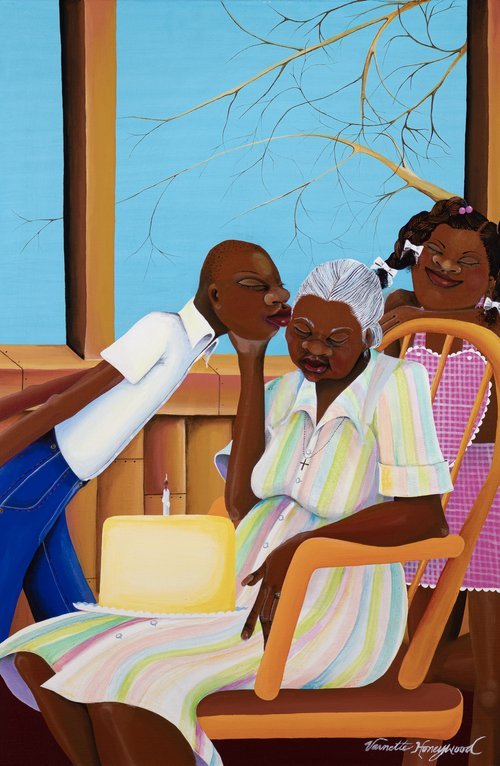

Varnette Honeywood

Among its participants, the 1960’s Black Arts Movement ignited an important cultural transformation, as many African American musicians, poets, writers, and visual artists turned their craft to addressing themes of Black pride, culture, and self-determination. The movement built on the artistic and cultural developments of the Harlem Renaissance, which took place in the 1920s and 1930s. Its central aesthetic architect, Alain Locke, first African American to win a Rhodes scholarship to Oxford, advocated for a reshaping of the African American image within the arts into a more positive, uplifting portrayal of the race. Moonwalking forward, the 1980s and 1990s brought to television several Black sitcoms in which living room walls draped with African American art honored the culture and implicitly sent a message about the possibility of transforming one’s living space into a cultural haven. This third renaissance of African American art included Varnette Honeywood (1950-2010), whose colorful works celebrated the joy, tenderness, and simplicity of Black lifestyles through assemblage, collage, drawing, and painting.

Honeywood studied fine art at Spelman College in Atlanta, where she earned her B.A. in 1974, and completed graduate studies at the University of Southern California, earning a M.S. in Education. Growing up in Los Angeles gave Honeywood the opportunity to develop a mentorship and friendship with the late Cecil Fergerson, who retired from the Los County Museum of Art as assistant curator. Fergerson became known as The Godfather of the Arts, organizing community exhibitions as well as advocating for and mentoring other African American artists.1 Scholar Paul Von Blum notes that Honeywood also received encouragement and support from such established artists as Ruth Waddy (1909-2003) and Samella Lewis (1923-2022).2

With acrylic on canvas, in Birthday (1974), Honeywood depicts a family album memory: youths honoring their grandmother’s birthday. A welcoming bubblegum blue sky with waving tree branches is framed by a living room window to set the tone for such an important theme. Sitting in a rocking chair wearing a carefully rendered cotton candy striped dress, this elder’s expression of gratefulness is surrounded by grandson’s suga kiss on her cheek and her granddaughter’s smile. The young girl’s coffee ebony hair braids complement the wise honoree’s grey hair bun. Using fabric, paper and found objects, Sabbath (1977) suggests the significant act of worship within Black culture. Reminiscent in theme of William H. Johnson’s Going to Church (1940-41), Honeywood references several cultural artifacts signifying the importance of this practice. For example, whether the Sabbath is interpreted as a Saturday or a Sunday, the three Black men in this work sport suits—striped blue, grey, and black. Of additional importance, one man carries a New Testament Psalms & Proverbs, the other holds a one-dollar bill, suggesting the value of both religious literacy and monetary support within the community. By contrast, three sistahs are graced in dresses—rose pink, ivory white and lemon yellow, each wearing hats. The figurative portrait profile in a single direction alludes to the focus and unity necessary for Black culture to not just survive, but to also thrive. Dixie Peach (1983) is a snapshot of that common kitchen ritual where matriarch mama or auntie is using the hot straightening comb for fixin' up a young girl’s hair. With beautified hues of coffee, cookie tan, and mocha, Honeywood simultaneously elevates the elegance of African skin tone variety and highlights community among women sharing and encouraging one another while doing hair as food cooks on the stove.

Ultimately, all three works demonstrate Varnette Honeywood’s proficiency as an interpretive figurative artist among such masters as Elizabeth Catlett, Charles White, Laura Wheeler Waring, Carolyn Lawrence, Ernie Barnes, Phoebe Beasley, Joanne Scott, Herman Kofi Bailey, Philomena Williams, and Charles Bibbs. Honeywood’s works testify to the unbreakable togetherness that represents the best of the culture—the rituals of practicing spirituality, honoring birthday memories, and valuing the communal aspects of haircare. In fact, her mastery of material and appropriation reflects that of a visual historian. To be sure, all three works affirm that Black lives have always mattered.

Richard Allen May III

1 Cecil Fergerson, interview with the author, 1997.

2 Paul Von Blum, Resistance, Dignity, and Pride: African American Artist in Los Angeles, (Los Angeles: CAAS Publications, 2004), 48.