Alma Thomas

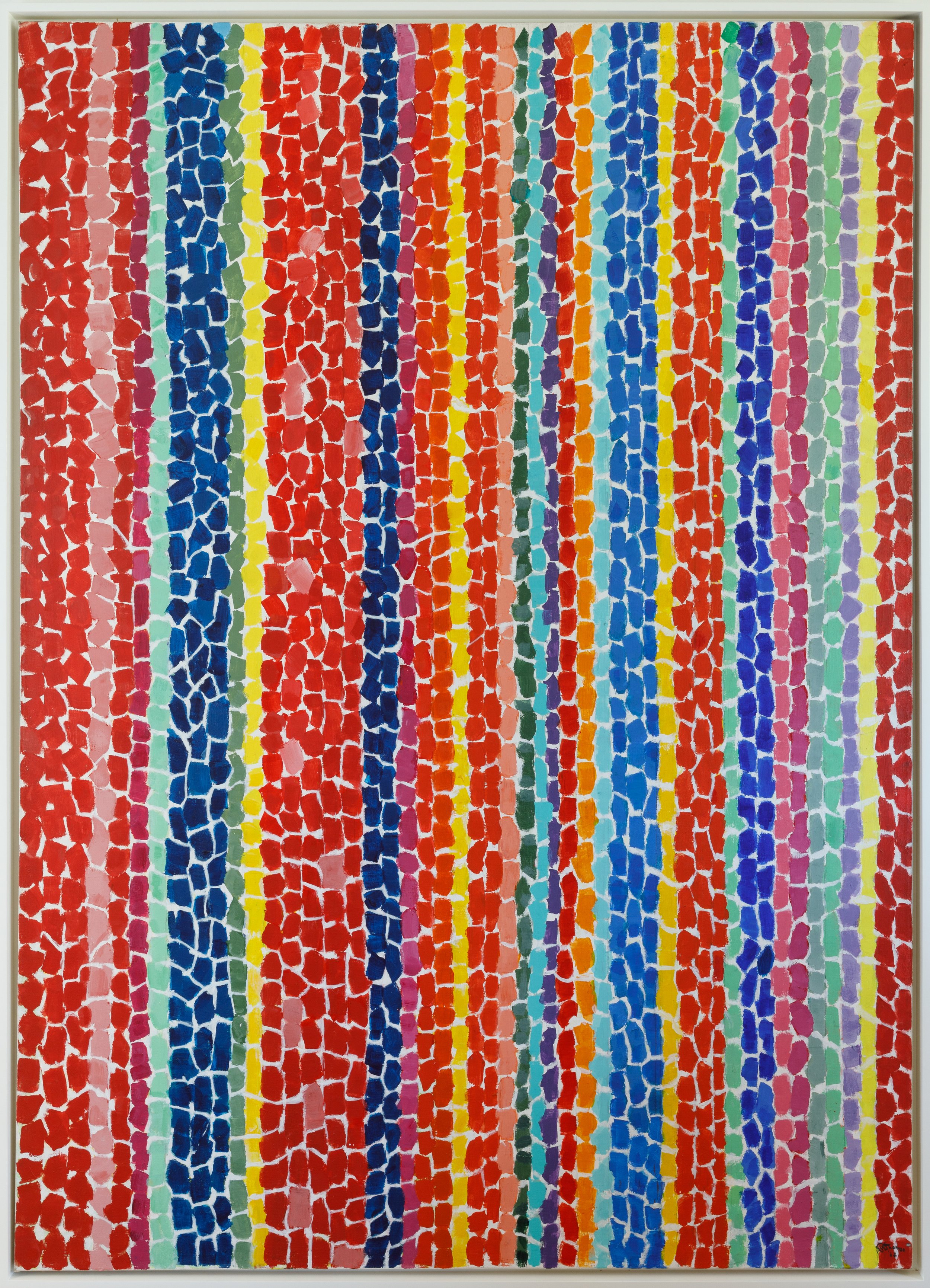

As the title suggests, Arboretum Azaleas Extravaganza (1968) bursts with vibrant colors pulled from the natural world and filtered through the sensitive eye of the artist. Cascading, undulating lines of color are broken up by the occasional glimpse of white, with shades of red, pink, blues, greens, yellows; they move from left to right and back again– in no particular order, and seldom repeated. Influenced heavily by her immediate surroundings in the nation’s capital – the National Mall, the U.S. Botanic Gardens, the National Arboretum, the Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens and her own home garden – the Washington D.C.-based painter Alma Thomas (1891-1978) is best known for her brightly-colored and jagged abstract compositions of the natural world. Like Augusta Savage (1892-1962), Emma Amos (1938-2020), Loïs Mailou Jones (1905-1998) and other Black female artists working in the early- to mid-twentieth century, Thomas worked primarily as an arts instructor for much of her life. Only after her retirement from teaching in 1960 did she turn to focus solely on her arts practice until her death in 1978. Like so many of her predecessors and contemporaries, Thomas was on more than one occasion a “first”– in 1924, she was the first Black woman graduate of the Art Department at Howard University; in 1972, she was the first Black American woman to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York; and in 2014, Thomas was the first Black woman artist to have a work acquired by The White House’s collection.1 An early supporter of the Black-owned Barnett Aden Gallery, founded in Washington D.C. by life and business partners James V. Herring (1887-1969) and Alonzo J. Aden (1906-1961), Thomas additionally held the role of vice president.2 A “first” of its own, Barnett Aden presented the work of Black and white artists alongside one another at a time when many Black artists were barred from exhibiting in mainstream arts institutions.

While Thomas studied with and worked alongside many of the Color Field painters and those involved in the Washington D.C.-based Washington Color School and Little Paris Group, her membership to any one group did not preclude her from finding her own unique artistic style. With the exception of some of the work she produced during her time as a student at Howard University (before later attending Teachers College at Columbia University in New York and American University in Washington D.C.), Thomas exclusively dealt in the realm of abstraction, a stance with which many Black visual artists and their allies took issue. In many ways aesthetically aligned with the mainstream Washington Color School and Color Field painters, Thomas’ work raised questions about the role of the Black artist at the time of immense social precarity, a rise in calls for racial equality and frequent protests. Countering this stance in an interview conducted two months before her death, Thomas stated: “I've never bothered painting the ugly things in life. People struggling, having difficulty. You meet that when you go out, and then you have to come back and see the same thing hanging on the wall. No. I wanted something beautiful that you could sit down and look at.”3

The turbulent 1960s and 1970s – the period in which The John and Susan Horseman Collection’s Arboretum Azaleas Extravaganza was created – is largely considered to be the height of Thomas’ practice, and includes many of the works for which she is best known. In the midst of significant world events such as the Black Arts and Civil Rights Movements, the Vietnam War and the Cuban Missile Crisis, Thomas proclaimed in 1970 that: “Through color, I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.”4 Informed in large part by her physical limitations brought on by severe arthritis in the early 1960s, Thomas pivoted her practice to illustrating colorful patterns she viewed outside of her window, initially utilizing watercolors and crayons.5 Art historian Charles Rowell characterized Thomas’ artistic period between 1960-1978 as: “...in no way representational or figurative; they were, in contrast to her earlier work, original abstract expressionist paintings—and they were so even when she first began to search for a style and subject and a voice commensurate with that she perceived, felt, knew, and imagined—all of those concerns that would ultimately define her as an artist.”6 Opting for the natural world over the human form, Thomas stood out amongst many of the Black visual artists of the period, due to her clear and recognizable artistic style, and her steadfast commitment to it. Rejecting legible depictions of the Blackness in her work, Thomas’ practice serves as a model for one way in which Black Americans have challenged monolithic and flattening representation, and continues to inspire the current generation of Black artists in the United States still facing many of these issues.

Heather Nickels

1 Jonathan Frederick Walz, “Alma W. Thomas: Unexpected Presence on the Global Stage,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 50 (2022): 102, muse.jhu.edu/article/863366 (Accessed 20 July 2023); Eleanor Munro, “The late Spring time of Alma Thomas (interview),” Washington Post, April 15, 1979 (Retrieved December 12, 2020), https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/magazine/1979/04/15/the-late-spring-time-of-alma-thomas/f205c bf7-3483-4cc4-8a52-7f5eacda7925/ (Accessed 21 July 2023).

2 Rowell, “Alma W. Thomas,” 1057.

3 Munro, “The late Spring time of Alma Thomas (interview),” Washington Post.

4 Charles Rowell, “Alma W. Thomas,” Callaloo 39, no. 5 (2016): 1043-1132, doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/cal.2016.0146 (Accessed 20 July 2023).

5 ibid.

6 Rowell, “Alma W. Thomas,” 1055.